One of the more intriguing paradoxes emerging from the rubble of the COVID-19 pandemic is new evidence suggesting that older adults—those at the greatest risk of severe illness and death from the virus—fared much better than their younger counterparts when it comes to coping with pandemic-related distress, anxiety, depression and social isolation.

“There’s been a lot of recent research exploring why the pandemic has had such a devastating psychological impact on adolescents and young people, but these studies tend to ignore the question of why distress levels have remained so much more stable in older adults,” said Sandra Hale, a professor of psychological and brain sciences in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Our study suggests that the degree to which adults’ distress levels changed during the pandemic was inversely related to their age—the exact opposite of what one might have expected based on age differences in the risk of severe negative consequences from infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus,” she said.

The study, published recently in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, offers further evidence that the pandemic is just one of many factors contributing to an ongoing surge in mental health problems among young people worldwide.

It also suggests that our ability to cope with stressors, such as the pandemic, hinges heavily on individual personality and emotional characteristics that change as we age.

“There is evidence to suggest that stressors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic may have come on the heels of an ongoing mental health crisis, potentially creating a perfect storm of psychological distress, especially among young people,” Hale said. “The pandemic focused our attention on how people were coping with distress, but our study shows that many of these mental health issues were already rising among young people before the pandemic and they would have continued increasing to near-current levels even without the pandemic.”

Co-authored by Washington University professors Joel Myerson, Michael Strube and Leonard Green, and undergraduate student Amy Lewandowski, all in the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences, this research is part of an ongoing series of studies on how aging and personality influence pandemic-coping behaviors.

One goal of the research is building a better understanding of how public health messaging can be improved and tailored to more effectively influence people in various demographics, such as age, gender and social status. For instance, in another recent study, the Washington University team found that fear messaging, which is intended to scare people and can increase their levels of distress, often may not be the most effective way to encourage people to change behaviors.

The current study, based on responses from thousands of people participating in long-running lifestyle and demographic surveys in the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom, found that distress levels among young and middle-aged adults in all three places rose steadily from 2015 to the pandemic.

For example, an analysis of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health found that distress among young people in the United States had been progressively increasing for some years up to and including 2019, and a similar trend was observed over the same period in the biennial survey of Household Income Dynamics in Australia.

Although the pandemic disrupted some data gathering for these ongoing surveys, the Washington University trend analysis suggests that distress levels would have continued to increase through 2020 even if the pandemic had not occurred.

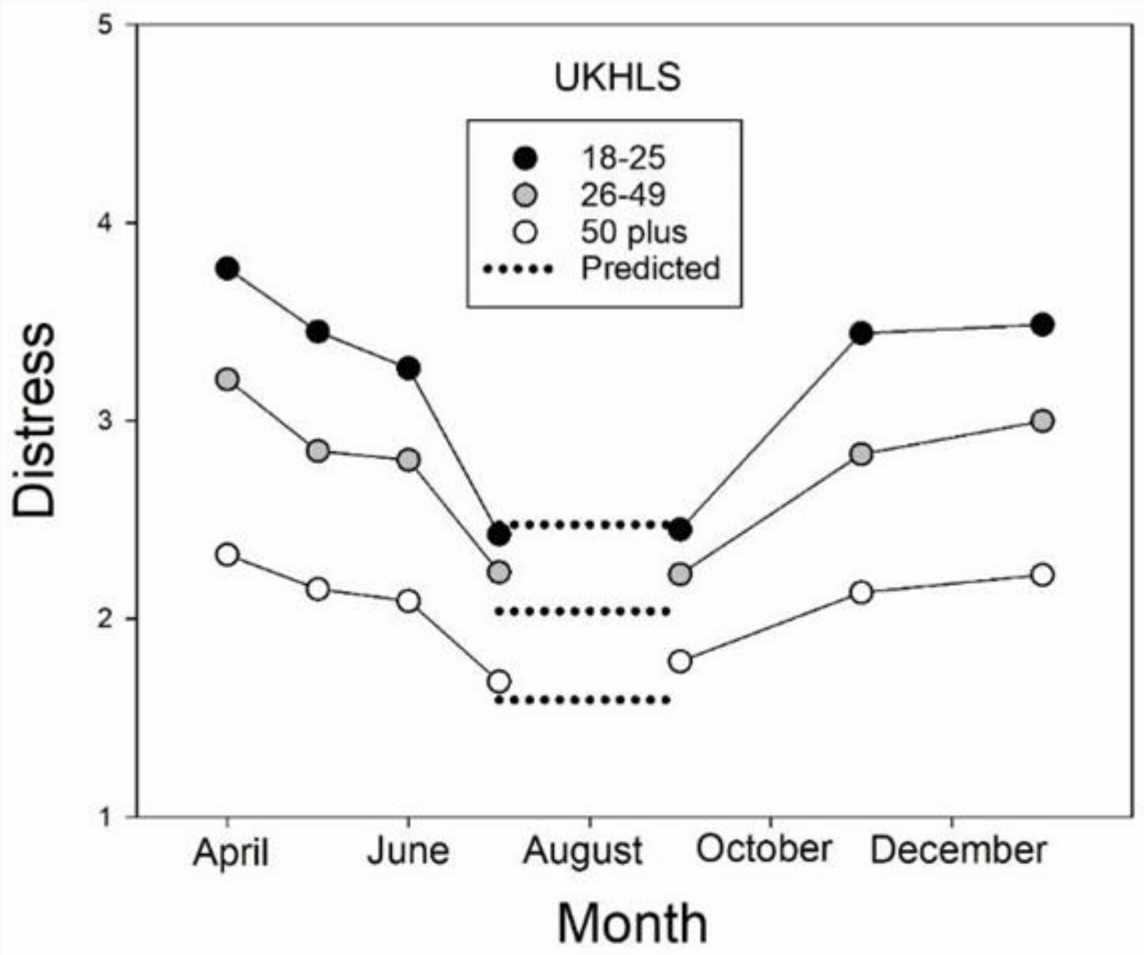

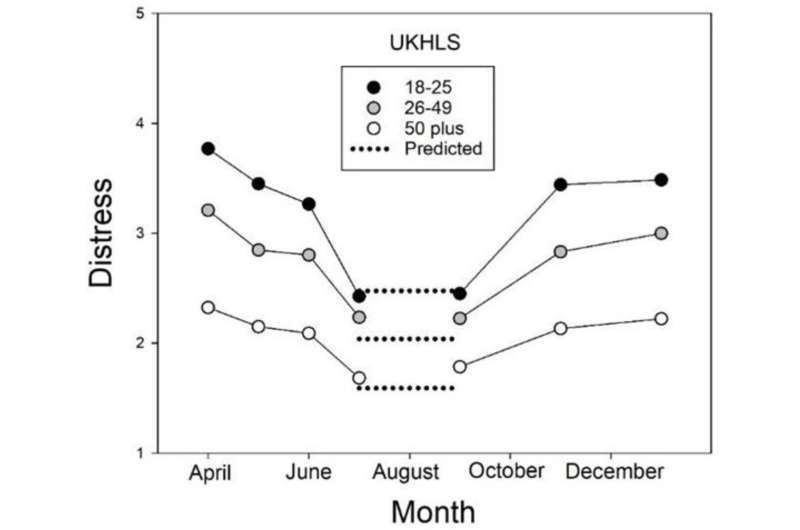

In the United Kingdom, the Household Longitudinal Survey continued to collect data throughout the nation’s two periods of extensive pandemic lockdowns in 2020.

The Washington University analysis found that distress levels between these lockdowns were close to those predicted from pre-pandemic trends and added distress during the lockdowns was likely related to social deprivation, as opposed to concerns about the pandemic per se.

Even though there is still no consensus as to what had been causing distress levels to increase prior to the pandemic, the Washington University analysis clearly shows that people appear to become less sensitive to stressors as they age.

The ability of older adults to remain resilient despite their higher risk of COVID-19 complications, the researchers suggest, is most likely explained by well-known, aging-related changes in personality traits, such as an increase in emotional stability.

The team is now exploring how aging-related changes in other personality traits, such altruism, sympathy and trust, also influence our response to stress.

“Our research suggests that it’s a mistake to think about the pandemic as one big event that affects all of us in the same way,” Myerson said. “Our data show that how we react to stressors depends on a whole range of individual personality and demographic factors, and that these influences may also push us in different directions depending on the current situation—whether we’re in the middle of a lockdown or at the beginning or end of a pandemic.”

“Even so, the end of this pandemic is not likely to put an end to the other stressors we face in our daily lives, so there’s a real need to better understand what distress means for people of all ages,” Myerson said. “Should the virus be controlled in the future, we may well be left with this pre-existing mental health crisis, and understanding its origins could be critical to dealing with it effectively.”

More information:

Sandra Hale et al, Distress Signals: Age Differences in Psychological Distress before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (2023). DOI: 10.3390/ijerph20043549

Journal information:

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Source: Read Full Article