Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

A combination of two monoclonal antibodies given as a subcutaneous injection prevented COVID-19 in patients at a high risk of infection due to household exposure, according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72% compared to placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serological testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

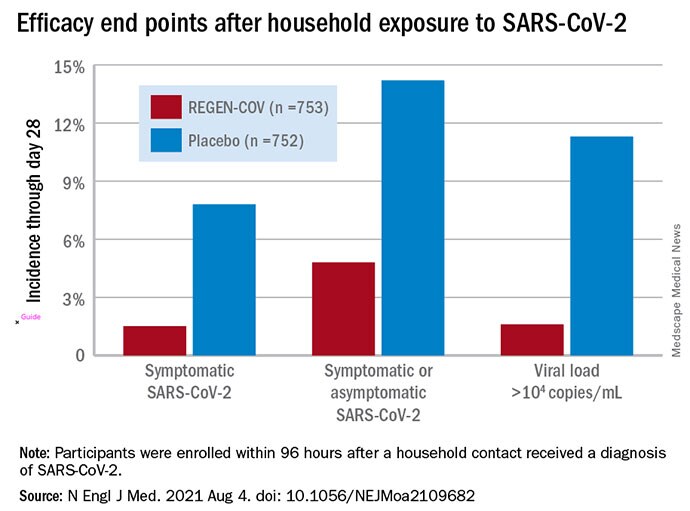

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (> 104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. Late last week the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The US government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Cohen agrees. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company, he said. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Wohl said. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Cohen and Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl have reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

N Engl J Med. Published online August 4, 2021. Full text

Donavyn Coffey is a freelance journalist who covers health and the environment from her home in the Bluegrass. Her work has appeared in Popular Science, Insider, and SELF.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. Here’s how to send Medscape a story tip.

Source: Read Full Article