Exercise is often recommended for maintaining and promoting good mental health, but some women find that a daily running routine can also provide specific tools for stabilising the peaks and troughs that come with bipolar disorder. While running isn’t a cure or solution, Rosie Viva found it to be a crucial stabilising aid. Here’s how she discovered the benefits.

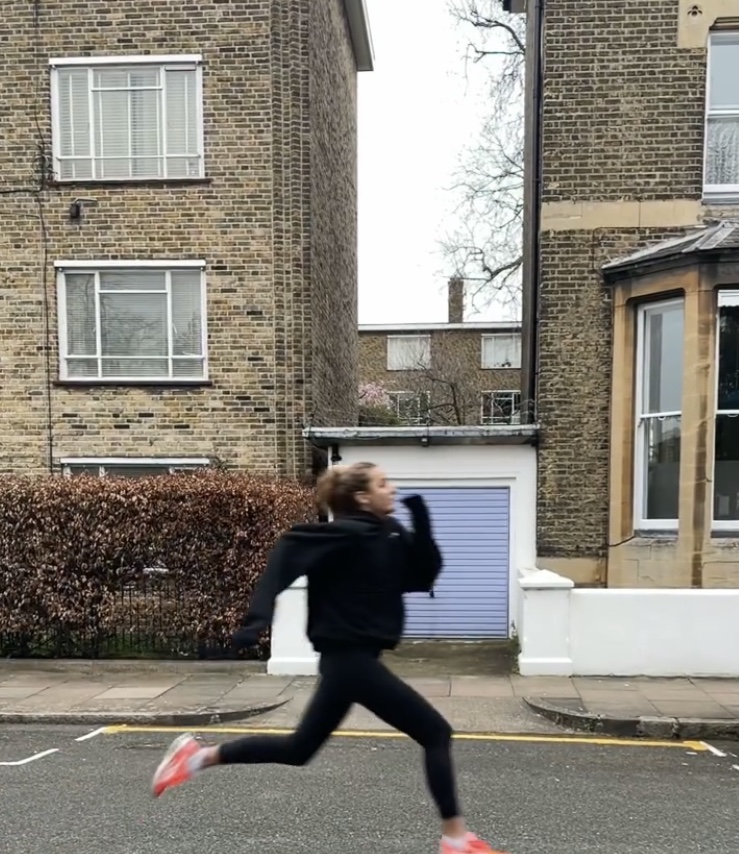

Rosie Viva was 22-years-old when she was first diagnosed with bipolar type I disorder. The diagnosis came after a psychotic episode which led to Rosie doing a stint on a psychiatric ward. Today, however, Rosie is healthy and happy, working as a model, business founder and presenter. As part of her recovery, Rosie runs every day – running being one of the helpful ways she’s been able to manage her mood and maintain mental stability.

Most days start with a long run – wherever she may be. Aside from the enjoyment aspect, Rosie tells Stylist that running is one of the only activities where there’s no competition or judgment from others. A big part of the appeal, she’s found, is that the only person you’re ever competing with is yourself: “Even if you don’t see improvement in your speed, you can improve in terms of how much you get out of it.”

You may also like

3 things someone living with bipolar disorder wants you to know about the mental health condition

Running to burn off extra energy

Rosie explains that it’s common for people with bipolar, especially those with type I, to have a lot of extra energy. She sees running as a healthier and more effective way to burn off that energy than, say, staying up late or going on hedonistic nights out. That’s because sticking to regular sleep patterns can be crucial for stabilising bipolar episodes, so late nights and hangovers can hinder recovery. “You can really tire yourself out with running, which will hopefully help you feel better and get you through those higher weeks without it going out of control,” she says.

Psychiatrist Yasamine Farahani Englefield explains how crucial having tools like this is: “We know that good exercise helps with sleep, and we also know that a good, regular sleep pattern is useful for people with bipolar. In fact, one of the early warning signs that someone (with bipolar) is becoming unwell is that they stop sleeping, so keeping that good sleep seems to be really helpful.”

The increase of energy that accompanies mania can also make activities that are recommended for mental health more difficult. Yoga and pilates, for example, are a struggle for Rosie, who finds them too slow and quiet. Instead, running is Rosie’s way of decompressing and slowing down her mind: “Running can be very therapeutic in that you’re repeating the same action again and again,” she explains. “It’s the one time I find I can make my thoughts quite still.”

Farahani Englefield says that that experience is totally in keeping with the evidence: “We know that exercise reduces stress, and stress is something that can trigger someone (with bipolar) to have a manic or depressive episode.”

What is bipolar disorder?

Bipolar is a psychological disorder that causes rapid swings in mood between extreme highs (mania) and extreme lows (depression). It can also trigger what is called a “psychotic episode”, which is when you may see, hear or experience things that aren’t real. A diagnosis of type I bipolar usually follows a period of mania lasting longer than a week, often one that results in psychosis.

Despite all this, however, most people living with the condition are emotionally stable in between periods of extreme behaviour and not everyone experiences psychosis or the most severe form of mania. While not curable, there are plenty of talking therapies, medications and lifestyle factors that can help to stabilise mood.

Running and bipolar – a scientifically approved therapy?

We know that exercise can have a positive impact on mental health and chronic issues such as anxiety and depression. Hayley Jarvis, head of physical health at mental health charity Mind, explains that exercise “is one of the first forms of treatment that should be offered by doctors for people experiencing mild to moderate symptoms of depression,” for example. While numerous studies have proved there to be a positive link between aerobic exercise and good mental health, however, far less data is available specifically for its effect on people with bipolar.

Could it be that bipolar is still an under-researched area of mental health? What little research does exist shows that exercise can improve the lives of people living with the condition. One systematic review looked at the results of 31 studies (including 15,587 patients) of exercise in bipolar patients. It concluded that “exercise was associated with improving health measures including depressive symptoms, functioning and quality of life,” but that more research was needed “to clarify the role of physical activity in bipolar patients.”

As with all things, however, you can have too much of a good thing. Preliminary studies have cautioned that too much exercise can be detrimental to bipolar patients – increasing their risk of a manic episode. As a result, it’s absolutely crucial that blanket exercise advice isn’t dished out and that people are encouraged to find out what works for them.

Social therapy

Running also helps to address the social isolation that Rosie has sometimes felt as a result of her illness. “There are so many aspects of my recovery that my friends can’t relate to, but I feel I have things in common with my friends when we go running or chat about it.” Even when running alone, she explains that “seeing other runners out gives that sense of community.”

Once you start to run at Parkrun or take part in a race, that feeling increases. “When you see how many people also benefit from [running], there’s something special about it,” Rosie enthuses.

Farahani Englefield explains that interacting with friends and family is a crucial element of staying healthy: “Patients who are socially isolated are more likely to have more relapses, more likely not to stay well, more likely to experience a decline in their function.”

It also helps to have people around you who know you well – by seeing them regularly for daily, weekly or even monthly exercise, Jarvis explains that they might be able to “recognise signs that you may be manic or depressed, help you look after yourself by keeping a routine or thinking about diet, listen and offer understanding, and help you plan ahead for a crisis.”

It’s not just the external elements that are helpful; running allows Rosie to check in with herself and notice changes to her mood. For her, manic periods are characterised by sensory elevations – brighter colours, richer smells, feeling in awe at her surroundings. By taking a similar running route most days, Rosie is able to better notice when things change.

During a manic period, she might start to experience an influx of gratitude that soon becomes overwhelming. This is clinically referred to as an “early warning sign”, according to Farahani Englefield, which can then help Rosie prepare to put measures in place that will help prevent her spiralling into a hypomanic episode or even mania. That may mean reducing her caffeine intake, letting her family and doctors know she’s feeling high, getting plenty of rest and sleep, and eating as healthily as possible.

While no one is saying that running is a cure or suitable for all, many runners rave about the fact that the act of putting one foot in front of the other can help to soothe thoughts and concentrate the mind. Rosie’s not alone in finding community, calm and self-compassion from running – something that many of us could benefit from, whether we live with a mental health condition or not.

Rosie’s top running tips

Don’t give up when the going gets tough

“When you do it as a one-off and try to run at the same level as your friends, it can be a knock to your confidence,” says Rosie. “Slowing it down and starting with something small like a 1km run is really important.”

Get outdoors

If running on a treadmill fills you with terror, it doesn’t mean that running isn’t for you. It’s a very different experience, according to Rosie, who always runs outdoors – usually through parks and by the river to connect with nature as much as possible in a bustling city. “What makes running so special is connecting with the outdoors,” she says.

A study by the University of Essex looked into the impact of regular doses of nature on mental wellbeing and found that 94% of people who took part in outdoor exercise activities said that green exercise activities played an important role in their quality of life.

Reduce your risk of injury

Injuries can have a detrimental impact on our mental health at the best of times, but exercising with bipolar means that you’ve got to move a little more carefully to avoid taking huge amounts of time away from your routine. Rosie takes care to listen to her body and only runs when she feels physically fit and well. She has also invested in sturdy trainers, which she recommends swapping out for a new pair every six months to avoid shin splints, painful knees and a sore lower back. She also carved out at least one rest day a week and alternates between shorter and longer runs to make sure she’s not overdoing it.

Be realistic – running isn’t a cure

Running helps Rosie to stabilise her bipolar, but she’s clear it’s not a fix or a one-size-fits-all therapy. “Focusing on stability is what helped my bipolar feel manageable,” she says, going on to explain that she maintains her mood with medication and lifestyle choices.

“Exercise, in general, really helped me get better and running is absolutely something that people with bipolar are capable of doing, even if you need to wait until you feel more stable to start.”

Rosie is currently working on a documentary exploring her experience of bipolar called Up In The Clouds which is due to be released later this year. If you’d like to know more about bipolar disorder and where to get help if you or someone you know is struggling, visit Bipolaruk.org or Mind.org.uk.

Looking to become a stronger runner? Head over to the Strong Women Training Club to join our four-week Strength Training for Runners programme.

Images: Rosie Vive

Source: Read Full Article